A secure middle class depends not only on workers earning fair and stable incomes but also on their ability to sufficiently save for the future. When families live paycheck to paycheck, unexpected sickness or layoffs can spark years of compounding hardships. But when families can build up savings, they not only are able to prepare for such emergencies but also to plan to buy a home, send their children to college, start a business, or switch to a career better suited to their skills and needs, all of which help ensure an economically more secure future.

A new Center for American Progress Action Fund analysis of data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, or SCF, shows that unions can play a role in increasing wealth for middle-class Americans.1 Union members generally have higher wages and better benefits than nonunion members, but these things alone do not explain why union members have more savings relative to their incomes than nonunion members.2 It is possible that stable union jobs that offer access to training and career opportunities make it easier for middle-class families to plan for their future and thus increase their savings. In that sense, union membership can create a virtuous cycle for middle-class stability.

As middle-class wages have effectively stagnated over recent decades—while the costs of important goods such as housing, health care, child care, and higher education have risen rapidly—it is not surprising that Americans are struggling financially.3 But the state of their balance sheets is shocking: Nearly half of all Americans who participated in a recent Federal Reserve survey reported that they could not pay for a $400 emergency expense without borrowing or selling assets,4 and 22 percent have zero or negative net wealth—meaning that they owe more than their assets are worth.5 And the degree of wealth inequality is much greater than income inequality: The top 1 percent of the United States, ranked by income, owns 37 percent of the country’s entire wealth, more than the bottom 95 percent of Americans’ holdings combined.6 Wealth inequality is also notable when measured along demographic lines such as race: In 2013, the median white household had a net worth 13 times higher than the median black household and 10 times higher than the median Hispanic household.7

One would expect that all of the good things that unions do to strengthen and grow the middle class—from raising wages to increasing benefits to encouraging economic mobility—would lead to more wealth for the middle class.8 Surprisingly, only a handful of researchers have explored the possible connection between union membership and wealth inequality. Jake Rosenfeld, professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis, the co-author of seminal research, has shown that the decline of unions has caused about one-third of the rise in wage inequality over recent decades. However, Rosenfeld explained in a blog post that there is much less information on how unions affect wealth, not income, inequality:9 “The comparative lack of evidence [about the possible relationship between unions and wealth disparities] does not mean connections do not exist, however, and a scattering of case studies and studies suggest that the destruction of unions in the U.S. may actually lie near the center of today’s yawning wealth chasms.”

This CAP Action analysis of Federal Reserve Board data, however, connects unions with more wealth among workers. The following data analysis provides some of the first empirical evidence that unions are associated with more wealth and thus more economic security for middle-class Americans. The data strongly suggest that strengthening unions is key to improving Americans’ financial well-being.

Data

CAP Action’s analysis uses data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances, a highly detailed and nationally representative survey of U.S. households that is conducted every three years and designed to capture all household assets and debts.10 The total amount of assets and debts calculated on the basis of the household information in the SCF captures the total amount of assets such as houses and stocks in the entire country and shows the distribution of these savings across population groups—for instance, between union and nonunion members.

For this analysis, workers are treated as union members if they are covered by a union contract. Wealth is defined as the difference between marketable assets—including financial assets such as checking accounts and mutual funds, primary residences, other real estate, and ownership in small businesses—and debt such as mortgages, credit cards, car loans, and student loans. Importantly, this measure of wealth does not count the expected value of income that people expect to receive from a defined benefit, or DB, pension.

The analysis only includes households with at least one wage and salary employee to make sure that it focuses only on households where members are working for an employer and could actually join a union.11 This allows for appropriate comparisons between union and nonunion households. The analysis further restricts the sample to middle-class households, defined as the middle 60 percent of the income distribution of families with nonretired heads of household between the ages of 25 and 64. Wealth is highly skewed, meaning that a disproportionate share of U.S. wealth is held by the wealthiest group, so that wealth comparisons for the entire population can be heavily influenced by the wealth held by the rich. By restricting the analysis to the middle of the income distribution, the data more accurately show the impact that union membership has on the wealth of typical workers.

Key findings

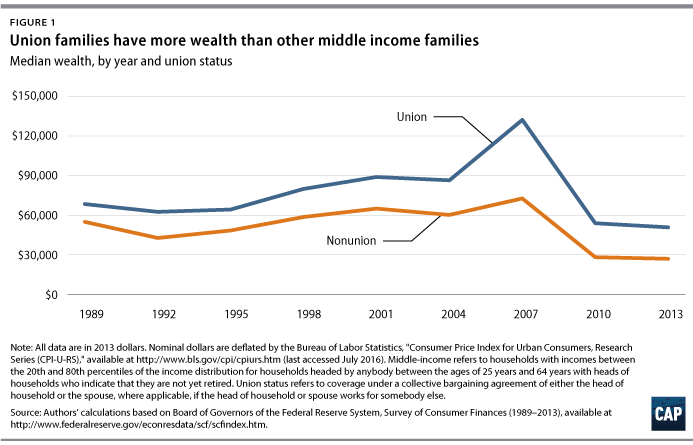

The data show that the median middle-income union household—meaning half of all union households have more and half have less wealth—typically has more wealth than the median nonunion middle-income household. This gap is apparent in each year since 1989, the first year for which consistent SCF data are available. (see Figure 1) In 2013, for instance, the median middle-class union household held $50,800 (in 2013 dollars) in wealth—nearly 90 percent more than the median middle-class nonunion household’s $27,000 in wealth. And this gap is not just an artifact of union households having higher incomes: The median union household has a higher wealth-to-income ratio than the typical nonunion household in every year analyzed. Put another way, union households have more wealth even after accounting for differences in income. Importantly, the CAP Action analysis also finds in every year that union households are less likely to have zero or negative net worth.

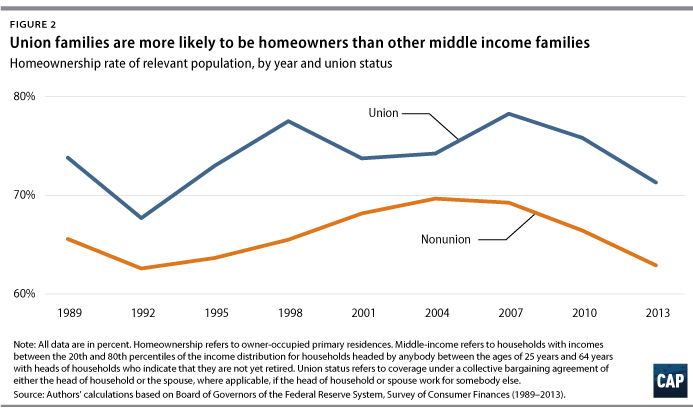

Housing makes up a large portion of the typical middle-income household’s total assets. The analysis summarized here finds that union households are more likely to be made up of homeowners than are nonunion households. In 2013, 71 percent of union middle-income households were made up of homeowners, while only 63 percent of comparable nonunion households were made up of homeowners. (see Figure 2)

While owning a home can be important for building wealth—in large part because it offers stability, access to strong communities, and eligibility for important tax incentives—families also need access to liquid short-term savings that they can access quickly in an emergency. These assets, stored away in easily accessible checking and savings accounts, for instance, help households deal with emergencies such as a broken-down car, a family member’s illness, or a lost job. CAP Action’s analysis finds that union households are more prepared for such emergencies, even though both union and nonunion households fall behind financial planners’ recommendations.12 The median union household in our sample built up $3,200 (in 2013 dollars) in 2013 in liquid savings, 28 percent more than the median nonunion household’s $2,500.

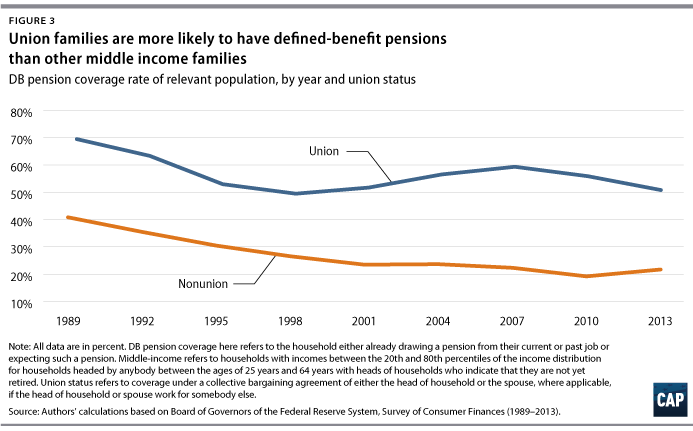

One of the largest—if not the largest—reasons for workers to save is to be able to enjoy a secure retirement that does not require them to choose between necessities, such as heating their homes and paying for their medications. The measure of total wealth used in this analysis only includes marketable wealth and thus actually understates union households’ retirement readiness, as it does not take the value of defined benefit pensions into account. The imputed lump-sum value of DB pensions is not readily available in the Survey of Consumer Finances and is often difficult to calculate. DB pensions guarantee a lifetime stream of income to people once they retire, reducing the necessary amount of other savings that people need to have to maintain their standard of living in retirement. As shown in Figure 3, the data show that union members are much more likely to have a DB pension from a current or previous job; these pensions substantially increase workers’ chances at a secure retirement. In addition to being more likely to have a DB pension, the median union middle-class household held $13,000 (in 2013 dollars) in savings in retirement accounts such as 401(k)s and individual retirement accounts in 2013, or more than three times as much as the median nonunion middle-class household. This means that the typical middle-income union member is better prepared for retirement than the typical nonunion middle-income worker because they have greater retirement savings and are more likely to have a DB pension.

It is important to note that the above figures do not incorporate controls to compare middle-class union and nonunion households, holding other important demographic characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, gender, and family status of the head of household constant. “Family status” refers to whether the head of household is married, a single man, or a single woman. However, the authors conducted supplemental analysis of household wealth that controlled for a host of factors—including age, race, education, family status, risk tolerance, and occupation. This analysis found that union status is associated with a statistically significant increase in total wealth, increased homeownership, and increased DB pension participation among middle-class households. Still, additional study will be important to determine the mechanisms by which union status and wealth correlate with each other. It is possible that increased job stability or better fringe benefits—such as family health insurance for union members compared with nonunion members—could contribute to more wealth.

Conclusion

Many Americans do not have enough wealth to pay for an emergency or to afford a secure retirement. The gap in wealth between the top and everyone else is staggering, vastly larger than the gap in income that often occupies policy discussions. And the chasm in household wealth has been growing alongside an increasing inequality of income and economic security. As a result, policymakers need to focus more attention on building the wealth of middle-class families. They can do so by instituting policies that directly help workers build wealth, such as by ensuring that all workers can access high-quality retirement savings accounts at work no matter their employer.13 Policies to help build wealth also can be more indirect, such as through incentives in the tax code. But policymakers need to create better-targeted tax expenditures to encourage middle-class wealth in areas such as housing and retirement because current U.S. policies to encourage asset building through the tax code are expensive and predominantly help higher-income taxpayers.14

These changes are not enough, however: Policymakers also need a broader conception of how to help families build up their wealth. That means working to raise incomes and control costs of key goods such as higher education and child care. And it also means protecting and encouraging workers’ right to join together in a union. CAP Action’s analysis shows that unions can help working people build their wealth and reclaim the American Dream of economic security during their lifetime and upward mobility for themselves and their children.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. David Madland is a Senior Fellow and the Senior Advisor to the American Worker Project at the Action Fund. Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the Economic Policy team at the Action Fund.

Endnotes