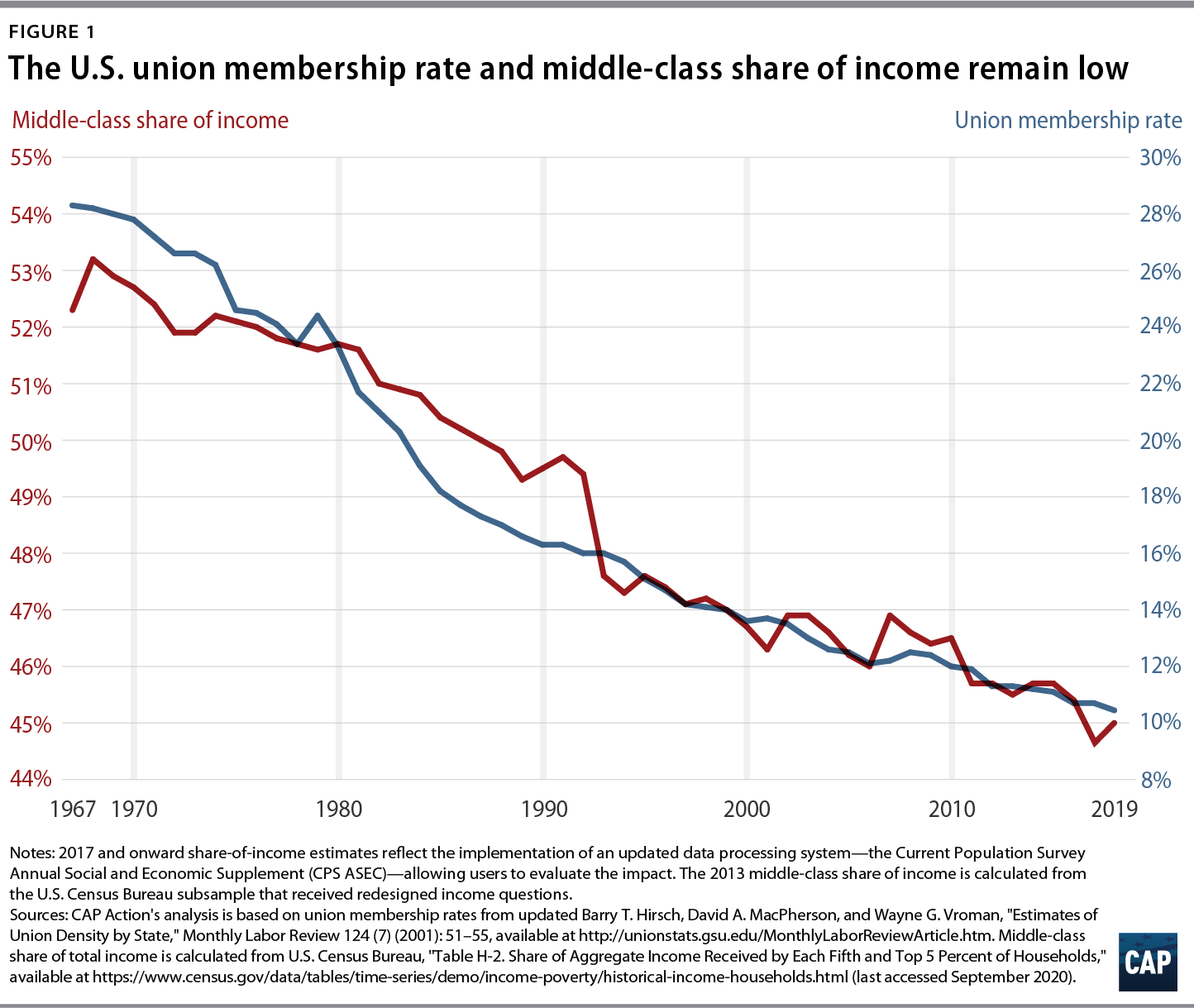

Unions play a significant role in addressing income inequality and creating a more equitable and democratic economy. As membership in unions in America has declined over recent decades, the wages and welfare of workers and America’s middle class have suffered. New data from the U.S. Census Bureau show a steady decline in the middle class’ overall share of income, paralleled by a significant decline in union membership. (see Figure 1) Compared with 1967, when 28.3 percent of American workers belonged to a union and 52.3 percent of national income went to middle-class households, in 2019, only 10.4 percent of workers belonged to a union and the middle class’ share of national income dropped to 45.1 percent. As families and workers have struggled to make ends meet during an unprecedented pandemic-induced recession, American billionaires have increased their wealth by $637 billion. Encouraging union membership and strengthening collective bargaining would play a major role in supporting the middle class.

Unions strengthen the middle class and help close divides

Unions raise wages for all workers. When unionized workers are compared with their nonunionized counterparts, analysis shows that union wages are about 11 percent higher, on average. Union participation has been shown to help address the gender pay gap: Hourly wages for women represented by unions are significantly higher than for nonunionized women. The union wage premium is even larger for some demographic groups, including Black and Hispanic workers and those without a college degree. Indeed, unions have been shown to narrow the racial wealth gap for families of color. From 2010 to 2016, nonwhite families who were union members had a median wealth that was almost five times as large as the median wealth of nonunion nonwhite families. Moreover, a recent study suggested that gaining union membership reduced racial resentment among white workers—something that is particularly relevant in America’s politically fraught environment.

Beyond increasing wages for workers, unions help secure good benefits, such as retirement plans and high-quality health insurance. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that union workers were more likely than nonunion workers to have retirement benefits in 2019. In addition, 85 percent of union workers participated in an employer-sponsored retirement benefit plan in 2019; the same could be said for only 51 percent of nonunion workers.

Data released through the Current Population Survey (CPS) this week highlight the long decline in the share of the nation’s income going to the middle class, defined as the middle three income quintiles. The data also help illustrate the close relationship between the fate of the middle class and the strength of unions. (see Figure 1)

Unions have been systematically attacked and weakened

Workers would like to join unions. A 2019 Gallup poll shows that 65 percent of U.S. adults approved of labor unions, as high as approval has been in nearly two decades. However, union density today is roughly one-third of its levels in the mid-1960s and is lower than it was before the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which granted workers basic union rights. Unfortunately, the law has become perverted so that it makes it unnecessarily difficult to join a union, allows corporations to fight unions, and does little when corporations break the law.

In recent decades, employers have become increasingly aggressive in their efforts to avoid unionization, and the majority of workers encounter serious opposition when they try to organize. “Right-to-work” laws, which prohibit labor unions and employers from requiring workers to pay union dues to cover the costs of negotiating a collective bargaining agreement or becoming union members at all, have become increasingly widespread; since 2010, six states have passed right-to-work laws. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Janus v. AFSCME effectively made the public sector right to work.

Actions to support collective bargaining

Despite these headwinds, workers are increasingly taking action. More workers went on strike in 2018 and 2019 than was the case for decades. The political landscape surrounding unions is also shifting. In the aftermath of the Janus decision, a number of states such as California, Oregon, and New York took steps to counteract the court decision and encourage public sector workers to join unions. In 2019, Nevada passed a law granting public sector workers the right to collectively bargain, and Colorado followed suit in 2020. While these actions have been led by progressive policymakers, there are signs that at least some conservative elites are getting the message: Over Labor Day weekend, a small group of conservatives, including Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) and former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, released a joint statement on the importance of unions, saying, “workers must have a seat at the table.”

However, it’s imperative that policymakers at the state and federal levels change policy to ensure that workers can join a union and bargain collectively. Federal policymakers should pass the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act and the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act and should also promote industrywide collective bargaining—which increases bargaining coverage and can further close racial and gender pay gaps. Sectoral bargaining also reduces economic inequality and boosts economic productivity. State and local policymakers can also take many steps to support unions. By focusing efforts on boosting unions, policymakers can more effectively rise to the current economic situation and bolster middle-class earnings.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Divya Vijay is a special assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Action Fund.