In the wake of the 2016 elections, politicians and the media have placed renewed interest on the policy preferences of so-called working-class Americans. A number of commentators interpreted the 2016 elections as a referendum by the disaffected white working class,1 spurring a focus on courting those voters. But in some cases, these narratives have relied on assumptions rather than evidence when it comes to defining the working class and identifying what types of policies are important to them. Policymakers are right to consider the policy preferences of working-class voters; just as importantly, they need to be wary of efforts that inaccurately portray the working class as racially homogenous or opposed to progressive policies.

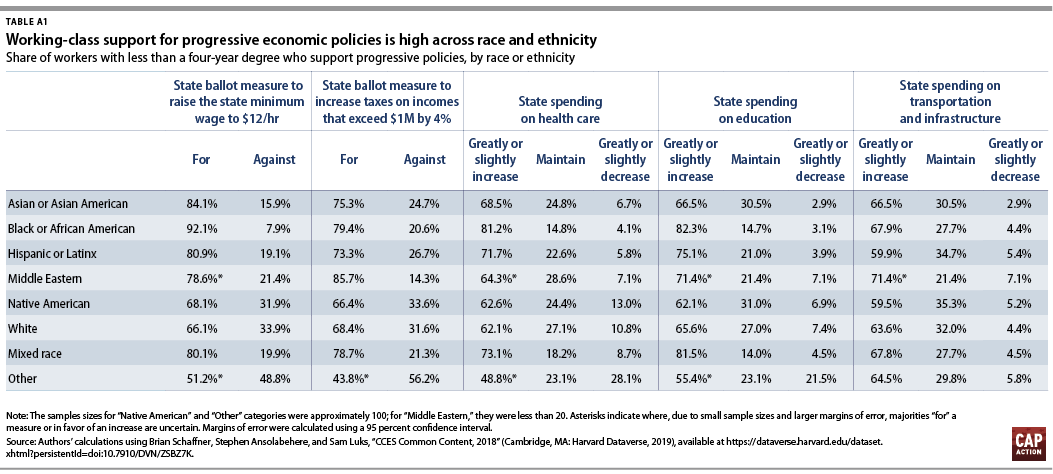

Previous research from the Center for American Progress Action Fund showed that, like college-educated workers, working-class Americans—defined as people of all races in the workforce without a four-year college degree—overwhelmingly support a range of progressive economic policies, including those to raise the minimum wage, ensure paid leave, increase spending on health care and retirement, and increase regulation of Wall Street.2 That research also confirmed that today’s working class is racially and ethnically diverse and that white, Black, and Hispanic working-class people all support these types of progressive economic policies.

This issue brief breaks down workers’ perspectives on economic policy by state. Using data from the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES),3 a nationally representative survey of 60,000 adults that provides a large enough sample for state-by-state analysis, the authors show that across the United States, members of the working class—as well as workers with additional education—support policies to raise wages, institute higher taxes on the wealthy, and increase spending on health care, education, and infrastructure.4 There are only a handful of instances in the authors’ analysis where both the working class and workers with a college education in each state did not favor progressive economic policy.5 The economic issues discussed in this brief are limited by the types of questions posed in the CCES survey and therefore are not entirely comprehensive.6 However, the responses do provide insight into what workers think about a number of current economic issues.

This issue brief does not break down state results by race and ethnicity due to sample size limitations. However, the data show that across the nation, the working class—whether white, Black, Hispanic, or Asian American—supports progressive economic policies, which is consistent with previous CAPAF research.7 (see Figure A in the Appendix) To be sure, there are certain policy questions on which attitudes of the working class diverge from those of workers with additional education8 and which workers’ attitudes are divided along racial lines.9 Still, there is strong consensus on the CCES questions that focus directly on workers’ economic interests. On most economic questions, members of the working class overwhelmingly support progressive policies, which suggests that policymakers could successfully implement these types of policies.

Today’s ‘working class’

For the purposes of this issue brief, the authors define the “working class” as members of the labor force without a four-year college degree. There is no singular definition of working class, and individuals self-identify based on a variety of factors including educational attainment, income, and occupation.10 While no classification is perfect, the authors chose to use education as the primary indicator in this study because it is more constant across people’s lifetimes.11 “College-educated workers” are defined as members of the labor force with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Roughly 60 percent of the American labor force12 and 63 percent of the electorate13 do not have a bachelor’s degree. As previously noted, today’s working class is racially and ethnically diverse. As of 2015, 13.7 percent were African American; 20.9 percent were Hispanic;14 and nearly half were female.15 The racial and ethnic demographics of the working class also vary significantly by state. For example, in Texas, nearly 40 percent of working-class respondents in the CCES study were Black or Hispanic. In South Dakota, 98 percent were white. The fact that members of the working class held similar policy views across states suggests that the types of progressive economic policies presented in this issue brief can unite workers across race.

The types of jobs held by the working class are also different than what is commonly assumed. Until the midcentury, a significant portion of people without college degrees worked in the industrial sector or in agriculture, forestry, and fishing, though even then, a larger share of the workforce was employed in the service sector. Today, about three-quarters of the noncollege-educated labor force works in the service sector.16

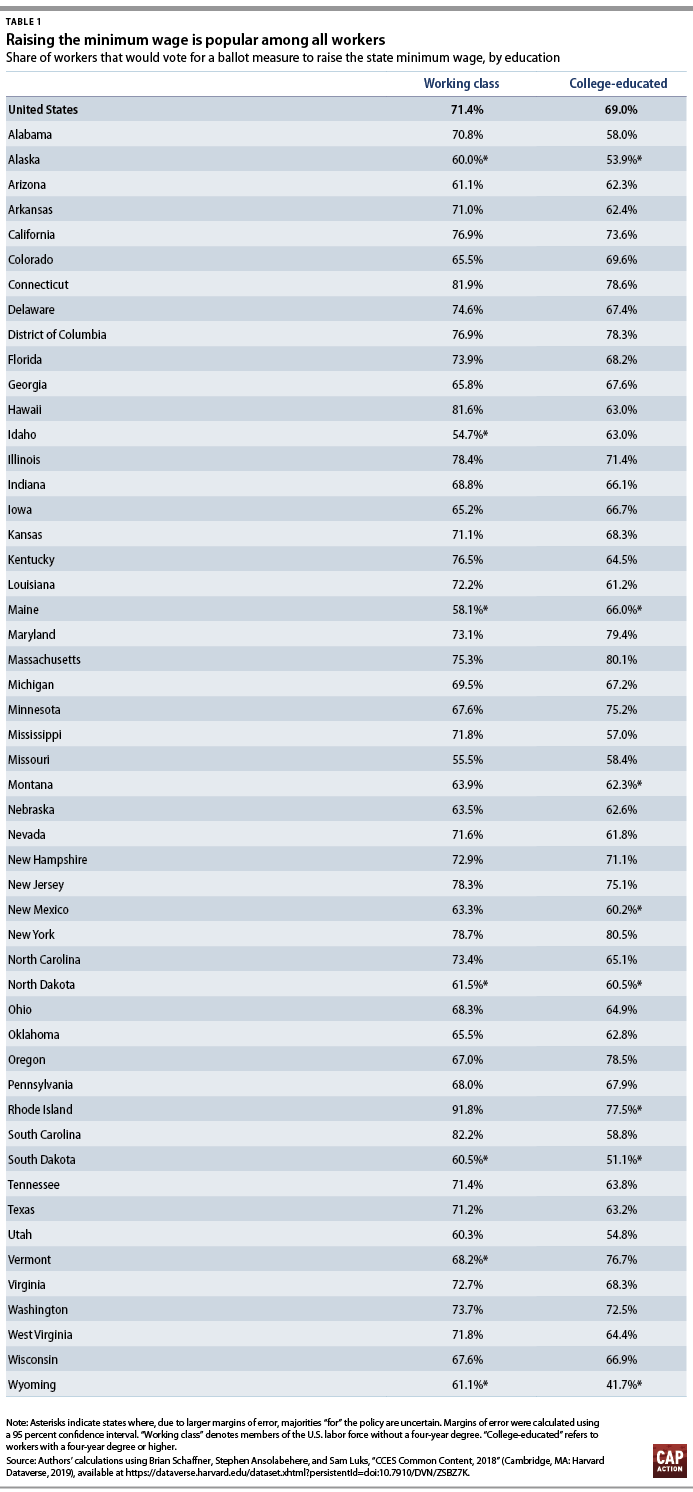

Working-class Americans support raising the minimum wage

In every state, a majority of the working class supports increasing the minimum wage. (see Figure 1) Indeed, the authors’ analysis of the CCES data shows that even in supposedly conservative states such as Kentucky and Louisiana, roughly three-quarters of the working class supports raising the state minimum wage.

Working-class support for raising the minimum wage should come as no surprise, given how difficult it is for most workers to get ahead in today’s economy. Typical U.S. workers make roughly the same amount today, in real terms, as they did 40 years ago.17 Between 1979 and 2018, productivity has soared while hourly compensation has barely budged.18 This gap suggests that economic growth has not translated to higher wages for most workers. Indeed, the share of economic output accruing to workers is near historic lows.19

The minimum wage—an important mechanism for increasing worker wages—has also failed to keep up with rising costs of living. Today’s federal minimum wage of $7.25 offers far less buying power than in the past, in large part because it is not indexed to inflation.20 In 2019, the federal minimum wage was worth 31 percent less than in 1968, when its inflation-adjusted value peaked, and 17 percent less than in 2009, when the federal minimum wage was last raised.21 If the minimum wage had risen at the rate of productivity, the Economic Policy Institute estimates that today’s minimum wage would be more than $20 per hour, using 2018 dollars.22 Evidence suggests that raising the minimum wage promotes overall economic growth, and research has shown that wage growth for low-income workers has been fastest in states that increased their minimum wage.23

Absent federal action, 27 states and Washington, D.C., have raised their effective minimum wage since January 2014,24 including traditionally “progressive” states such as Washington and California, as well as other states such as Nevada, Missouri, and Arkansas.25 However, state action to increase the minimum wage leaves behind far too many others.26

The CCES survey asked respondents about a $12 minimum wage; however, many recent proposals have set the minimum even higher. For instance, in July 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Raise the Wage Act, which would increase the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 and give up to 33 million workers a raise. Furthermore, the Raise the Wage Act and many state policies eliminate the federal subminimum wage of $2.13 per hour for workers with disabilities and workers who receive tips as well as index future minimum wage increases to inflation so that workers do not lose ground each year.27 While the authors are not aware of comprehensive state-level polling data on this topic, national-level surveys have found that two-thirds of voters in surveyed congressional districts favor a $15 minimum wage.28 Taken together, these data indicate high levels of support for a higher minimum wage across states.

While the CCES survey did not ask about other policies that would raise workers’ wages, such as those that would make it easier to join a union, national-level polling suggests that pro-union policies would also be broadly popular.29

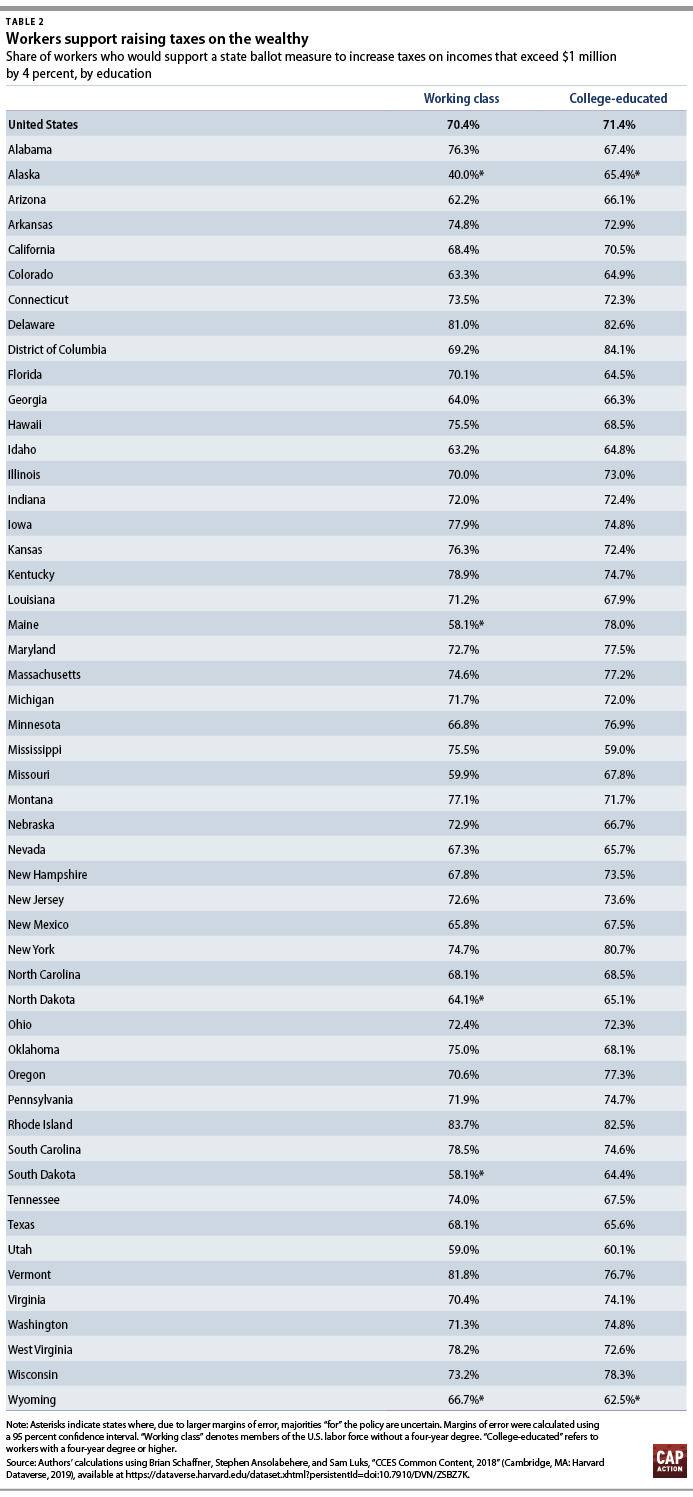

Working-class Americans support taxing the wealthy more

In addition to showing support for higher wages, the data indicate that members of the working class consistently support equitable economic policies more broadly. For example, the vast majority of the working class agrees that high-income Americans should pay higher taxes.

Income inequality in the United States is near record highs. While the middle class continues to struggle, America’s wealthiest households are taking home a larger share of national income than in recent decades and now hold an even larger share of wealth.30 More progressive tax policies that distribute income and wealth away from the very top toward programs that benefit middle- and low-income earners would help correct the imbalance of economic—and accompanying political—power.

By cutting tax rates for the wealthy and corporations, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) only worsened inequality in the United States.31 Under the TCJA, the average taxpayer making more than $1 million will pay almost $70,000 less in taxes annually—more than 122 times the average tax cut received by households earning $40,000 to $50,000 per year.32 When the individual tax cuts expire in 2027, the scale will tip even further, with the top 1 percent of households receiving roughly 83 percent of tax benefits from the bill.33

According to CCES data, a majority of working-class respondents in every state except Alaska said that they would support increasing taxes by 4 percent on incomes that exceed $1 million in order to pay for schools and roads. The majority of college-educated workers in every state also support higher taxes on the wealthy. These findings point in the same direction as previous national-level CAPAF research, which found that the majority of working-class Americans favored policies that increase taxes on high-income Americans.34

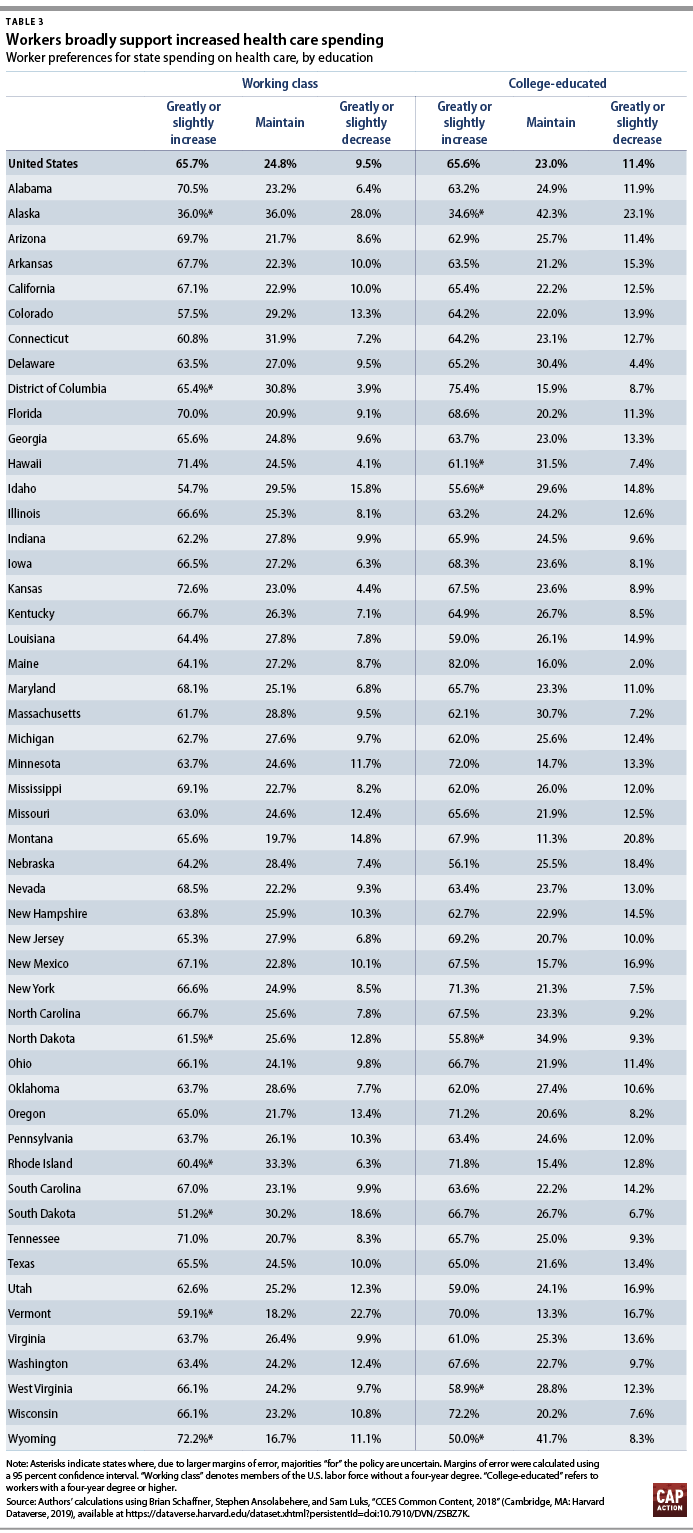

Working-class Americans support investments in health care, education, and infrastructure

In recent years, several conservative state legislatures have pushed through large budget-cutting measures at the expense of social programs.35 However, CCES data indicate that workers in every state oppose cuts to health care, education, and infrastructure spending and instead overwhelmingly support greater investments in these areas.36

According to CCES data, in all states but one—in which there was plurality support—the majority of working-class respondents support increasing spending on health care.

Currently, 27.5 million Americans lack health insurance.37 Despite widespread public support for universal coverage,38 conservative policymakers in many states continue to attack existing health care programs and laws that protect patients.39 As a result, the uninsured rate increased in eight states—Michigan, Washington, Ohio, Alabama, Tennessee, Arizona, Idaho, and Texas—from 2017 to 2018.40 The latest lawsuit to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) could further imperil health care access41 and result in 20 million more Americans becoming uninsured.42

While several states have taken steps to combat conservative assaults on health care,43 access to health care for millions of Americans is still precarious. Nearly 2.5 million low-income people are uninsured because their states did not implement the federally funded option to expand Medicaid under the ACA,44 and other states have imposed burdensome work requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries.45 Among Americans who do have coverage, about 30 million are underinsured, meaning that they lack adequate financial protection against health care costs.46 While conservative policymakers often argue that expanding coverage is too expensive,47 the CCES data indicate that workers overwhelmingly support investing more in health care, not less.

The same is true of education. With the exception of one state, in which there is plurality support, the majority of both college-educated and noncollege-educated workers in every state and in Washington, D.C., support increasing state spending on education.

More than 90 percent of K-12 funding for education comes from the state and local levels.48 However, many states still have not recovered from steep cuts to education spending made in the wake of the 2008 recession. Making matters worse, 7 of the 12 states with the biggest cuts to education have since chosen to cut taxes, which can have further implications for state education budgets.49 In addition to state and local cuts, the Trump administration has also sought to decrease federal investments in education.50

Money matters when it comes to education. Teachers’ salaries and benefits comprise the majority of public school spending.51 Smaller education budgets force local districts to hire fewer educators or cut teacher pay. A large body of research shows that greater spending leads to higher-quality education and improved outcomes for students.52 Additionally, underfunded schools and low salaries may be causing fewer people to enter the teaching profession.53 CAPAF’s analysis of CCES data—which show overwhelming support for increased state spending on education—suggests that recent trends of educational divestment are likely unpopular among workers at all education levels.

Another area with significant spending shortfalls is infrastructure and transportation. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that the gap between anticipated needs and spending, accounting for all levels of government, will grow to $2 trillion over the next 10 years.54 Investments in infrastructure and transportation are essential to a well-functioning economy, because they ensure that citizens are able to live healthy lives and access jobs, essential services, and educational and social opportunities.55 In the coming decades, infrastructure spending will need to do more than maintain and repair existing structures. New telecommunications technologies will need to be deployed, particularly in rural and other underserved areas.56 Furthermore, forestalling catastrophic climate change will require rapid decarbonization and a fundamental transformation in the way U.S. transportation and infrastructure systems function.57

Luckily for policymakers, workers are united in their support for increased infrastructure spending. In every state and in Washington, D.C., the majority of workers without a college degree prefer increasing spending on transportation and infrastructure.58 And in most states, less than 10 percent of noncollege-educated workers support a decrease in spending.

Conclusion

In an era of wage stagnation, uneven access to health care, and historic levels of inequality, many working-class families find themselves in a precarious economic situation.59 As a result, the working class is pushing for policies that will increase economic well-being and stability. CCES survey data suggest that workers across the United States—whether they have a four-year college degree or not—support policies to raise wages, institute higher taxes on the wealthy, and increase spending on basic investments such as education, health care, and infrastructure.

Not all workers support these policies, and the degree of support varies across states. Still, the data suggest that in the overwhelming majority of states, members of the working class—as well as workers with college educations—express strong support for progressive economic policies.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Malkie Wall is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Action Fund.

Appendix

Authors’ note: CAPAF uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.”

Endnotes