Pundits and policymakers are increasingly talking about the importance of reaching out to working-class Americans. Unfortunately, discussions of the working class are too often based on assumptions and stereotypes rather than evidence about who makes up the working class and what they want. Previous research from the Center for American Progress Action Fund showed that the working class—defined as the members of the labor force without a four-year college degree—is much more diverse than it is typically portrayed: It consists of large numbers of women, workers of color, and service-sector workers as well as the often-discussed white men in goods-producing industries.1

This issue brief examines workers’ opinions on economic policy using data from four major nationally representative surveys.2 Research for this brief shows that working-class whites, blacks, and Hispanics want elected officials to make the economy work for better for them, as do college-educated workers. Workers broadly support, for example, increasing the minimum wage; broadening access to paid leave; passing equal pay legislation; expanding access to health care and retirement benefits; making college more affordable; regulating banks; and instituting higher taxes on the wealthy. 3

Survey data details

This brief uses survey data from four major surveys conducted in 2016 and early 2017: the General Social Survey (GSS), the American National Elections Study (ANES), the Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES), and the American Values Survey (AVS).4 The GSS, CCES, and AVS are nationally representative samples of American adults. The ANES is a nationally representative sample of American adults who are eligible—but not necessarily registered—to vote. Note that the analysis in this issue brief is limited to workers, and as such the authors further restrict each sample to include only individuals who report being in the labor force.

As outlined above, this brief focuses on workers’ attitudes toward various economic policies. For the purposes of the brief, the term “working class” includes members of the labor force with less than a four-year college degree. There is no agreed-upon or clear definition for the working class, as individuals’ class self-identification is dependent on their education, income, and occupation.5 But an education-based definition is used for this analysis because education is more stable across one’s lifetime than income or occupation.6

Due to sample size constraints, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) members of the working class are not shown in the figures in this analysis, though results from the CCES—which has a much larger overall sample than the other surveys—are discussed when available

There are some political issues—most notably views on racial discrimination and immigration—where workers’ views diverge along race and class lines. For example, a significant percentage of white working-class workers harbor racial resentment and support anti-immigrant policies such as banning immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States.7 Politicians seeking to scapegoat people of color and immigrants for American economic woes could harness and amplify these views.

Of course, this does not mean that progressives should compromise their support for policies that counter systemic inequities and help ensure fair treatment for people of color and immigrants. While the economy is not working well for many workers—especially those without college degrees—nonwhite workers in the working class often fare even worse than their white counterparts due to long-lasting structural disadvantages.8 In 2017, just 2.5 percent of Americans with a four-year college degree or more were unemployed.9 The average unemployment rate among white workers with less than a college degree was 4.6 percent in 2017.10 For black and Hispanic members of the working class, the unemployment rate was 9.1 percent and 5.6 percent, respectively.11 Progressive economic policies are especially key for these workers.

The bottom line from the findings of this analysis is that supporting a bold economic reform agenda does not involve trading off the support of one group of workers for another. Workers—especially those without four-year college degrees—face real economic challenges.12 They also support progressive economic policies that would make the U.S. economy work better for the working class. Broad and proud advocacy for these policies can serve to unite workers across class and race.

Workers support policies to raise wages and improve working conditions

Considering that many workers struggle to get ahead in today’s economy, it is no surprise that they support policies that serve to raise wages. People at the top of the income distribution have pulled further away from working- and middle-class families: Despite decades of economic growth, the typical worker brings home roughly the same hourly wage as they did 40 years ago in inflation-adjusted terms.13 Institutions that serve to protect workers’ economic interests in both the workplace and political arena—namely, labor unions—have been under attack from corporate interests and state lawmakers for decades.14 Today, just 6.5 percent of private-sector workers are union members15—meaning that fewer workers have the power to demand and receive higher wages and benefits than in the past—even though the majority of Americans approve of labor unions.16 And the benefits of collective bargaining are often highest for workers without a college education and for workers of color.17

Another labor market institution that protects fewer workers than in the past is the federal minimum wage, which has remained stagnant at $7.25 per hour since 2009. While 29 states and the District of Columbia have established higher state minimum wages than the federal minimum wage, nearly 4 in 10 workers live in states where the minimum wage remains $7.25.18

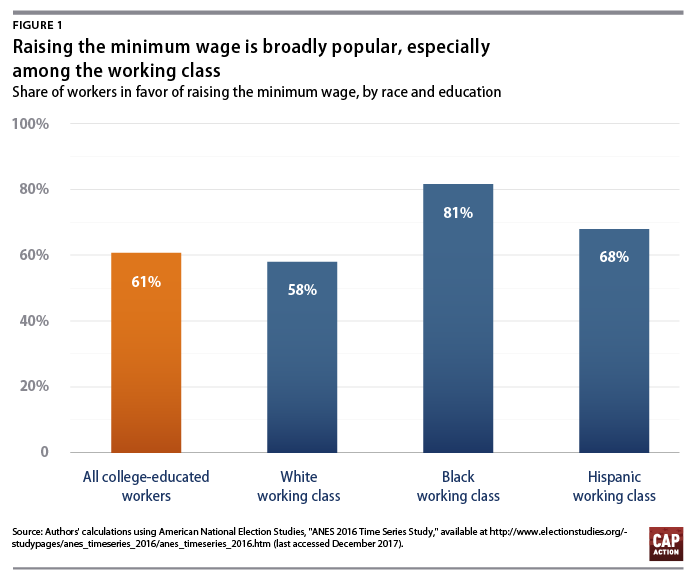

Ending the nine-year slide in many minimum-wage workers’ purchasing power by raising the federal minimum wage is broadly popular among workers. Data from the ANES found that 61 percent of college-educated workers and 58 percent of white working-class workers support raising the minimum wage.19 Black and Hispanic members of the working class show even higher levels of support, with 81 percent and 68 percent in favor of increasing the minimum wage, respectively.20

A similar pattern of support for increasing the minimum wage is found in data from the 2016 CCES. College-educated workers and white working-class workers expressed roughly the same level of support—65 percent and 64 percent, respectively.21 Overall working-class support was higher than that of college-educated workers due to overwhelming support from black, Hispanic, and AAPI members of the working class—90 percent, 81 percent, and 80 percent, respectively.22

Workers are also broadly supportive of policies to make it easier for parents to participate in the labor market and combat the gender pay gap.

The Family and Medical Leave Act, which passed more than 25 years ago, provided workers for the first time with unpaid job-protected family and medical leave to take time off for the birth or adoption of a new child or to care for their own illness or that of a loved one. Yet only 6 in 10 workers have access to this unpaid leave.23 In addition, the United States is the only advanced economy that does not have some form of guaranteed parental leave policy.24

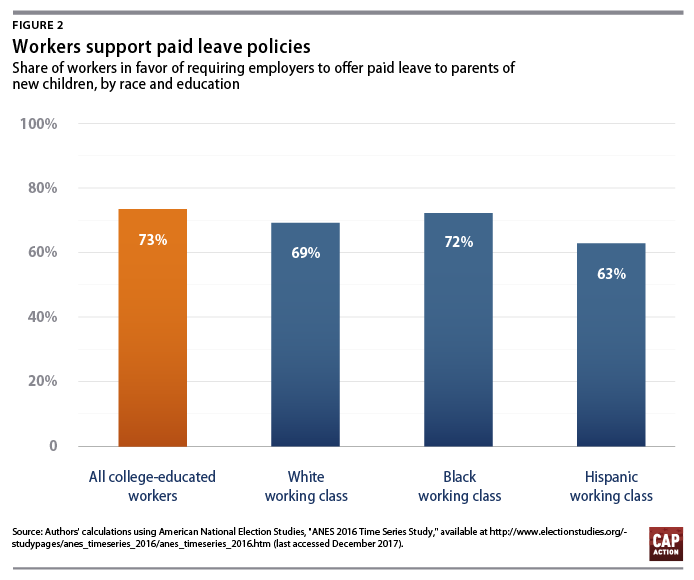

Today, just 15 percent of civilian workers—and just 6 percent of low-wage workers—have access to paid family leave.25 As a result, working families lose an estimated $20.6 billion in wages each year from being forced to quit working or reduce their work hours—and this does not take into account the potential long-term consequences of unemployment.26 Data from the ANES show that members of the working class are broadly in support of expanding access to paid leave, with support across racial and ethnic groups ranging from 63 percent of Hispanics to 69 percent of whites to 72 percent of black workers. 27 Support from college-educated workers stands at 73 percent. 28

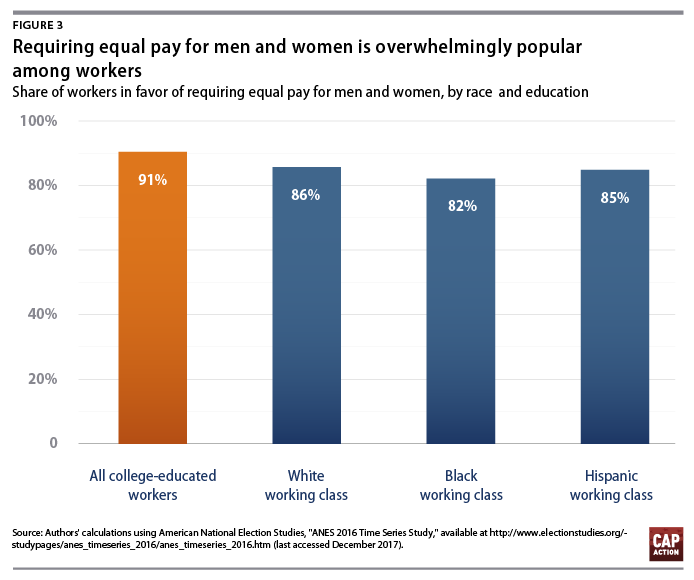

Similarly, there is broad support for policies to ensure that women receive pay that is equal to men’s. Equal pay for equal work is a key tenet of any commitment to equality and fairness. Overall, women only make 80 cents for every dollar made by men.29 The pay gap between men and women exists at all education levels30, and the pay of women of color—more so than that of white women—falls even further behind the pay of white men.31

These pay disparities undermine women’s and families’ economic security. Therefore, it is no surprise that policies to close the gender pay gap are broadly popular across education level and race. The vast majority of white, black, and Hispanic workers without a college degree—as well as the majority of college-educated workers—support equal-pay policies.32 While there are laws on the books that are intended to ban pay discrimination, they have not been updated as necessary to ensure they properly govern today’s workplaces.33 In order to protect workers, policymakers should consider policies that hold employers accountable for inequitable practices and that ensure transparency, such as those banning prior salary information requests in the hiring process or requiring the inclusion of salary ranges on job postings.34

Workers support investing in health care, retirement, and education and regulating Wall Street

In addition to showing broad support for policies to improve workers’ wages and benefits, data clearly show that workers back government action to ensure Americans have health care and a secure retirement; to make public college more affordable; and to safeguard the U.S. financial system.

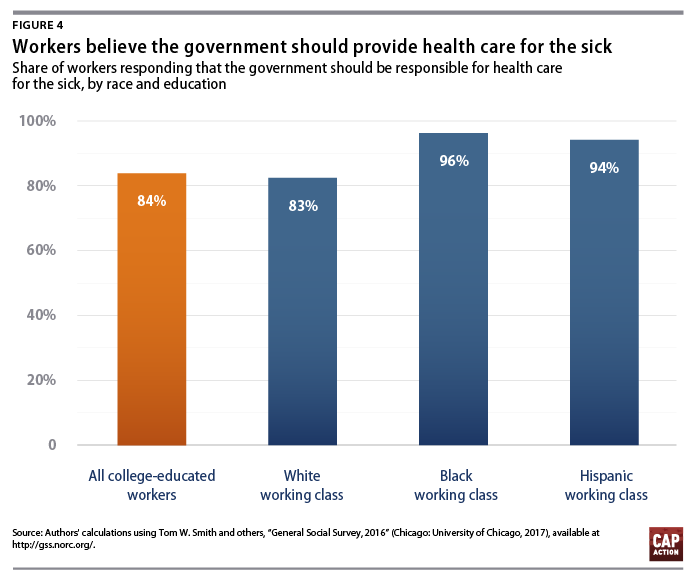

The vast majority of workers believe that it is the government’s responsibility to provide health care for those who are sick. According to the 2016 GSS, more than 4 in 5 college-educated workers and members of the white working class stated that the government “definitely should” or “probably should” be responsible for providing health care.35 Black and Hispanic members of the working class are even more likely to have this view than members of the white working class.36

Despite broad public support for government-provided health care, however, the current congressional majority has proposed massive cuts to health care programs. Its fiscal year 2018 budget resolution proposed $1.8 trillion in cuts to health programs—slashing Medicaid, Medicare, and Affordable Care Act subsidies.37 And while this budget did not threaten Social Security retirement benefits, many conservative policymakers are making it clear that Social Security will be soon targeted for cuts. 38

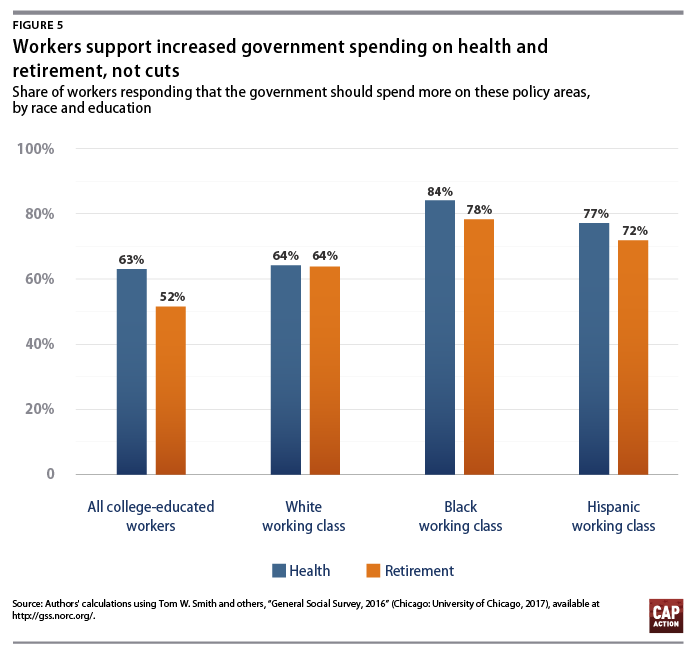

Yet when workers are asked if they prefer cutting or increasing spending on government health care programs and retirement programs, they predominantly want increased investment—not cuts. Seventy-one percent of workers without college degrees would prefer the government spend more on health care, and 67 percent of these workers would prefer increased spending on retirement programs as well. College-educated workers similarly prefer boosted spending, with 63 percent supporting more health care spending and 52 percent supporting more spending on retirement benefits. Polling from GBA Strategies and the Center for American Progress this year similarly shows broad-based opposition to cuts to programs that protect Americans’ living standards, including Social Security Disability Insurance, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.39 This polling also found that white, black, and Hispanic members of the working class oppose so-called work requirements in Medicaid that would allow states to take Medicaid away from workers who are not currently employed or participating in a government-approved training program.40

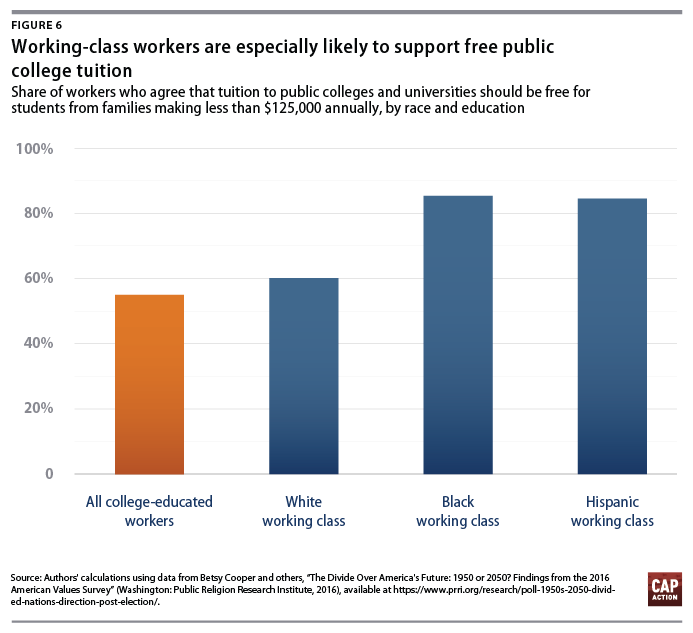

Workers also support policies to make public college more affordable. The rising cost of higher education has made it more difficult for individuals to finish college. Driven in part by declining state spending on higher education in recent years, the average tuition for a public four-year college grew by 289 percent—even after adjusting for inflation—from 1980 to 2014.41 While community college tuition has not grown as fast, many students there struggle to afford basic necessities such as food.42 The majority of workers support policies to address this issue and to increase access to higher education by providing free tuition programs at public colleges to families making less than $125,000 per year.43 Workers of all races without college degrees are more likely to support this policy than workers who currently have a college education.44

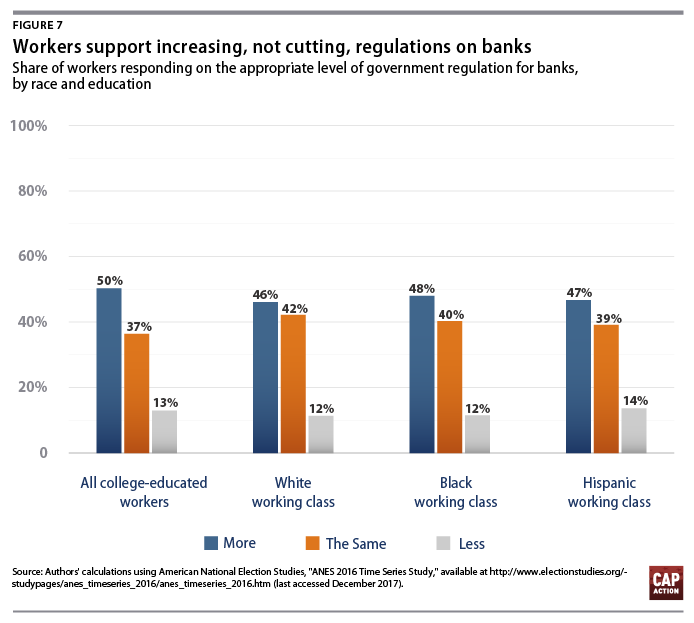

While there has been a degree of bipartisan support for bank deregulation in the current session of Congress45, workers are united across racial and class lines against reducing bank regulation. Among those without college degrees, 46 percent of workers support more banking regulation and 12 percent favor less; views are similar regardless of race.46 College-educated workers are similarly opposed to reducing regulations on banks. This shows that principled opposition to bills such as the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act—which rolls back enhanced regulations from the Dodd-Frank Act for 25 of the 38 largest banks in the United States—would be both a political winner and good policy.47

There is broad and overwhelming support for raising taxes on the rich

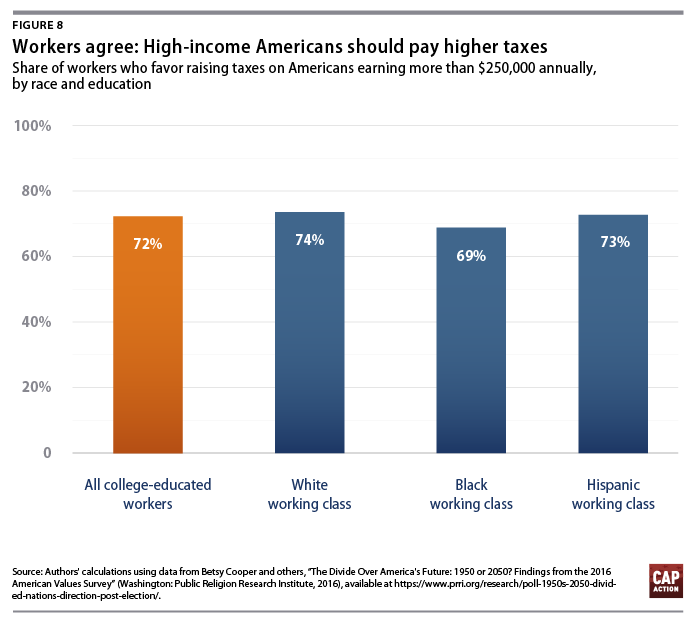

Regardless of race or education levels, raising taxes on high-income earners is very popular among workers. According to 2016 AVS data, the majority of working-class workers of all races, as well as college-educated workers, support instituting a new tax on those making more than $250,000 annually.48 Members of the white working class are the most supportive, with 74 percent in favor of raising taxes on these taxpayers.49

Data from the ANES similarly show broad support for raising taxes on the highest earners. More than 3 in 5 white, black, and Hispanic workers in the working class favor raising taxes on those making more than $1 million annually.50 College-educated workers agree, with 69 percent in favor of such a tax increase and only 16 percent in opposition. 51

Despite this broad support for raising taxes on the rich, in 2017, policymakers chose to do the opposite. President Donald Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which passed into law on Decemer 22 despite unified Democratic opposition. Under the TCJA, the average taxpayer making more than $1 million annually will receive a $69,660 tax cut—more than 122 times more than the average tax cut received by families earning between $40,000 and 50,000.52 In 2027—once the bill’s individual tax cuts expire and its corporate tax cuts remain—members of the top 1 percent will take home 83 percent of the benefits.53 Policymakers should keep in mind the massive popularity of raising taxes on the wealthy when considering future changes to the tax code.

Conclusion

Many Americans believe that the economy is not working well for them. Indeed, nearly 80 percent of the working class thinks the economy unfairly favors the wealthy.54 Americans without four-year college degrees, regardless of race or ethnicity, support policies to ensure that their jobs pay more and provide necessary benefits; to increase financial regulation and spending on health, retirement, and education; and to raise taxes on the wealthy. And these views are generally held by college-educated workers as well.

To be sure, some members of the white working class hold views on race and immigration issues that enable workers to be more easily divided by politicians who stoke racial resentment and xenophobia. Promoting a strong progressive economic agenda, therefore, may not be a panacea to win the support of all workers. But the results are clear: The majority of workers—whether white, black, or Hispanic, and whether college-educated or not—want politicians to push for progressive economic policies.

Alex Rowell is a policy analyst for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at CAP Action.

Endnotes